|

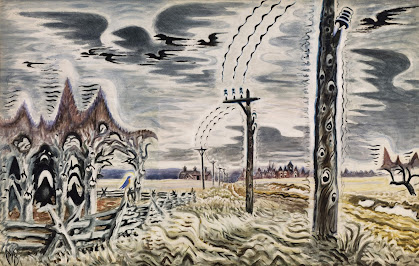

| Song of the Telegraph (1952), watercolor on paper, 53" x 34" |

Charles E. Burchfield lived in the Great Lakes region of the US, born in Ohio then moving to Western NY to reside in West Seneca, a suburb of Buffalo, NY. His body of work presents a keen interest in the immediate environment where he grew up and then lived later in life, employing an approach that is not the traditional western representation and borders on the fantastic in some instances.

So, there is a challenge to critics in evaluating Burchfield as Art historians find it difficult to place him into a category: Surrealist? Superrealist? Magic Realism? None of these fit his imagery since there is no direct line evident in any of his drawings or paintings and, as many Art critics or historians will do, they find it easier to pass off Burchfield’s work as “Regionalism” or pronounce that he was a “regional artist.”

That’s not a bad description necessarily—I’d be happy if any art critic even bothered to say that about me—but this label tends, if not intended by the critics deliberately, to demote the artist as someone who was not following the prevailing or influential styles of their time and bounded out along on their own personal journey that is too idiosyncratic. Not bringing together the styles current of the artist’s time simply makes it more difficult to comprehend someone who is unique.

One may think that those in the Art world would welcome this kind of creativity but instead, and unfortunately, it becomes the albatross around the neck of the artist. The creative originality is not thought of as intriguingly fresh but as “regional” or “eccentric.” That’s too bad, since many will take these kinds of criticisms as pertinent to the artist’s work without considering that the imagery provides a fresh perspective.

Admittedly, in my college days as an art student I wasn’t thrilled by Burchfield’s work. I thought that some of the paintings and drawings caught the essence of urban and rural landscapes of Western New York (we like to capitalize the “W” so as to make it a distinctive geographic title). Still, on the whole I was puzzled that he did not try to push a bit more into the other new ways of his era in order to apprehend a subject through the visual art.

And that’s exactly what is good about Burchfield, while he did draw upon other streams of depicting the world he made them his own. Today, I appreciate his vision. Not only plants and building, but even insects make their way into view; I know that there is more to Art than re-presenting insects, but even those who are more traditional landscape painters rarely give them the spotlight.

There are still a few drawings and paintings within the Burchfield oeuvre that just do not attract me. On the whole, however, I see him as an outstanding artist who presented another vision of reality.